Here at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, InFocus weeks are meant to bring the entire class together for a few days to get exposure to a variety of things depending on where we are in our educational timeline. Our first InFocus experience came after a whirlwind nine weeks of scratching the surface of understanding the human body—otherwise known as “Structures.” We now know all of the bones in the body (triquetrum anyone?), can visually distinguish between an osteocyte and an osteoclast, and can officially say that we know how babies are made. I’ve felt simultaneously challenged, energized, and so grateful to be here.

This first InFocus week served as an opportunity to learn about community health, health disparities, and clinical research, but it was also an opportunity to catch up with friends, to have meetings with mentors and advisors, and to take a mental break before starting a new challenging course.

We started each of our InFocus days with a taste of clinical research, which is something that yours truly was largely unfamiliar with. Terms like case fatality rate, relative risk, and recall bias have become a part of my vocabulary, new things for me to wrap my mind around. Though I don’t plan to make clinical research a part of my future career (though one never really knows), it’s good to have a grasp of this material so that I can navigate through a journal article with relative ease. The rest of our days were spent either in large lectures or small groups focusing on the health of East Harlem and the various approaches that people from a multitude of disciplines use to understand and work through some of the most longstanding issues facing the community. Among other things, we had sessions on the effects that racism, incarceration, and healthcare systems have on the well-being of urban communities, such as East Harlem. After outlining these issues, the sessions gave some examples of effective mechanisms of action such as education, health system design, and improvement cycles.

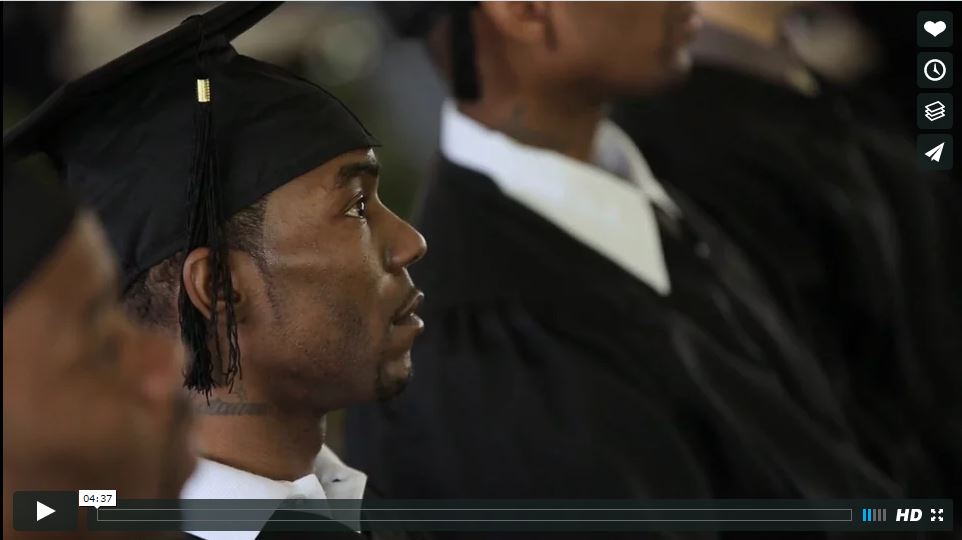

During the week, we were lucky to have a number of guest lecturers, and I think the rest of the class would agree with me when I say that Robert Fullilove, EdD, Associate Dean of Community and Minority Affairs at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, gave one of the best lectures that we’ve had since starting medical school. During the InFocus session, “East Harlem Health and Beyond: An Introduction to Health Disparities and the Historical Context,” Dr. Fullilove focused on how incarceration is a huge factor on the health of both the incarcerated and the communities that they’ve left behind. During the session, we tackled intellectually- and emotionally-charged questions such as: Who is most likely to be incarcerated? What kinds of healthcare—if any—do prisoners have access to? What happens to the families and friends who are left behind? Although these are difficult questions to answer, Dr. Fullilove not only unpacked their complexity for us but also managed to inspire us by talking about some of the work that he has been doing with the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), an organization whose mission is to provide college-level education to people serving their sentences at six New York State prisons. It’s a stunningly simple concept: Educate those who nobody has believed in, those who haven’t believed in themselves, and they will be the ones who will become the change agents in their communities. Empowerment ultimately leads to better health and a better life for the individual and for those that their work will touch.

Dr. Fullilove concluded his lecture with a video of a BPI Commencement. (Winton / duPont Films).

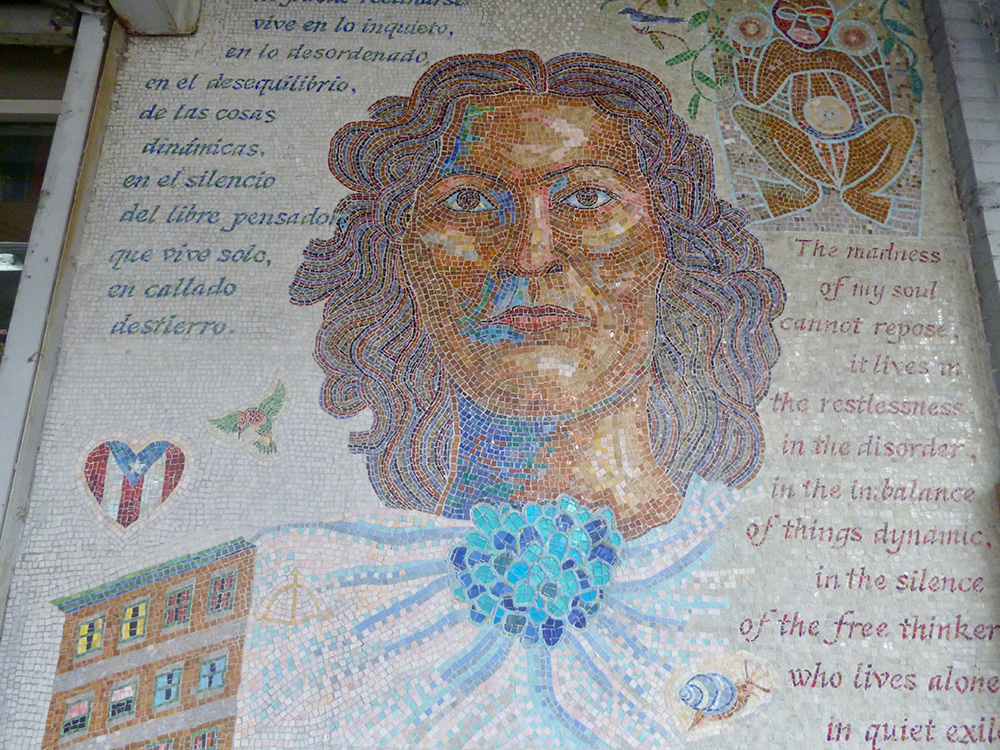

Another session that left me invigorated was our field trip out in the community to understand what local organizations are doing to help mitigate some of the issues that we discussed in lecture. We had a choice of what we wanted to see, and if you know me, you know that anytime I get to interact with art, I’m there. So my decision was an easy one: “Lost and Found Murals of East Harlem” run by East Harlem Preservation’s Kathleen Benson Haskins, a retired Museum of the City of New York educator and curator. We were also lucky to have Manny Vega, an artist who has contributed a number of works to the community, join us to give us insight on his motivation for working in East Harlem.

World renowned mosaic muralist Manny Vega in #EastHarlem sharing with @IcahnMountSinai students. #InFocus pic.twitter.com/FIQzlv2rQg

— Reena Karani MD,MHPE (@docrck) October 19, 2016

Manny talked about his own life story beginning in the Bronx and how he came to own his identity as an artist. He talked about how art has empowered him and inspired him to empower others in New York City and beyond. When he creates something, he’s leaving a positive mark on the community that people can gather around and enjoy. His work makes people stop in their tracks, pay attention, and share in the magic with others. Also, Manny’s works, similar to the others that we saw in the community, feature important figures for the residents of East Harlem such as Julia de Burgos, Oscar Lopez Rivera, and Che Guevara as well as scenes and symbols of everyday life.

You may be thinking that this is all great, but what does it have to do with health? Everything. Art is healing, both in its creation and consumption. I can’t tell you how many times that I’ve been in a difficult place in my life and have turned to art to help me work through what I’m feeling. Art is also healing on a community level because much of the health of a neighborhood has to do with people’s sense of ownership of their surroundings. This is especially the case when thinking about how gentrification, something that East Harlem is currently undergoing, often erodes a community’s identity. When someone like Manny comes in and creates works about the things that the community cares about, it not only gives people a sense of pride, but also anchors that precarious identity.

During the week, there were a number of great moments like the ones that I’ve talked about here, and the big take away for me is that we as medical students—and the physicians that we will become—have a lot of power to help chip away at some of the most challenging issues facing healthcare and humanity. It’s a tall order. The work is often unglamorous, exhausting, and heartbreaking, but it is work that we can be proud of—a legacy that we can leave behind for others to build upon. And who knows? Maybe we’ll even get our very own mural.

Slavena Salve Nissan is a first-year medical student and an aspiring physician-writer who can never have too many love poems in her life. She is the student leader of Sinai Arts, a contributor for the AAMC’s Aspiring Docs Diaries, and a medical student editor for in-Training.

You can find her poetry, photography, and thoughts on social media @slavenareina on Instagram and Twitter.