In a way, choosing medicine felt easy. My father is a family physician who exposed me to the field very early. I remember how exciting it was to hear him tell stories about work and explain the strange journals on our kitchen table. His unfailing commitment to his patients and his genuine sense of fulfillment always inspired me.

As I grew older, his stories gained more detail and nuance. Then when I was a teenager, I learned how morally and socially complex the physician role can be. In coming to America from Nigeria, my dad had to deal with a host of biases towards black people he had never encountered before. Despite being a nationally recognized medical student in Nigeria, he was just a black man with a strange accent in suburban Illinois.

The effects were usually subtle: patients would more frequently inquire about where my father trained or more frequently challenge my father’s recommendations for their care. However, some patients were so disquieted by a black, foreign physician that they would even request to be seen by another doctor.

At that point in my life, hate and prejudice were not new concepts: From micro- (people touching or grabbing my hair without consent) to macro-aggressions (the infamous six-letter-N-word), I had seen my fair share. Yet, this was different. Hateful kids at school can be avoided, shunned, or escaped. Hateful patients are another story entirely. Every time, my father treats those patients to the best of his ability. Every time, I must do the same, regardless of how uncomfortable it will feel to have a patient who does not want me as their doctor.

Chuma gives back by mentoring minority and underserved high school students who are interested in pursuing a career in medicine.

Some people are not used to seeing black people in positions of esteem or authority, so when they do, they instantly become uncomfortable. In some people’s minds, black people aren’t supposed to be doctors. What bothers me the most about such oppressive notions are their inevitable effects on young people of color. As society doubts us, we doubt ourselves, too.

Being black and successful in America first requires us to summon the strength to claw our way out from the pit of self-doubt society has dug for us. I was very lucky to have my father as an example—always helping me want and expect more from myself. But I cannot forget those who are not so lucky. One does not need to run through the statistics to remind themselves of how hard things are for many black people in the United States.

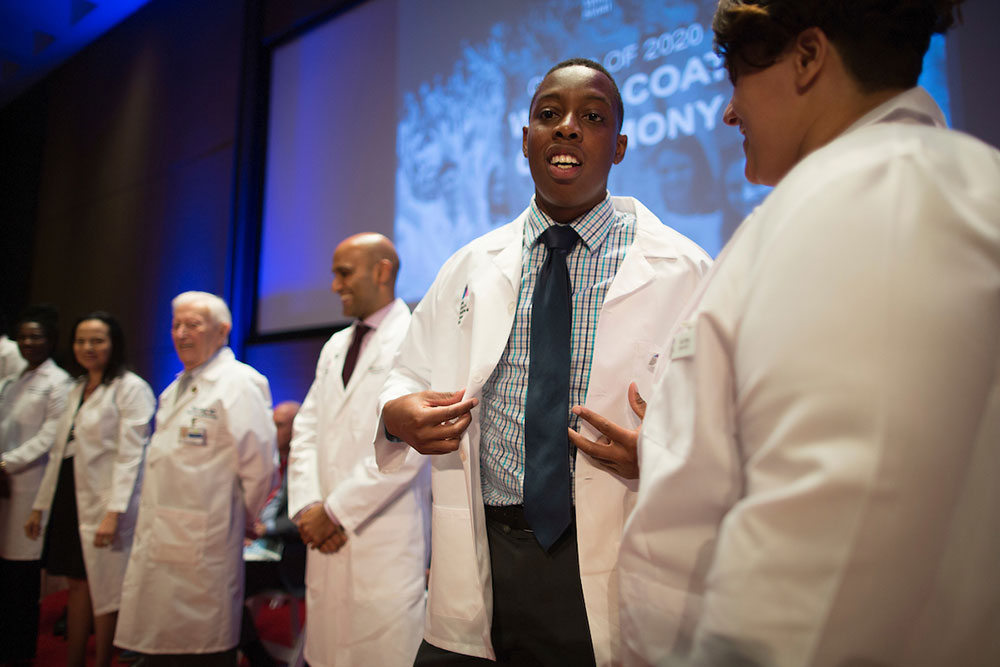

Therefore, as a black person in such a privileged position, I feel called to do what I can, to be visible and tangible to people who look like me. I currently fulfill this call by mentoring high school students through a program called MedDOCs here at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Giving back takes time, but it’s not my choice it’s my duty. And that duty makes my time in medical school all the more meaningful.

Chuma Nwachukwu is a first-year medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. He completed his undergraduate studies at Harvard University. In his spare time, he engages with a variety of community service projects, plays soccer, and competitively powerlifts.