I met Marlene when her dreams were interrupted at 5 a.m. Monday morning. She opened her eyes to a swarm of white coats crowding around her bed. She then weathered a few minutes of rapid-fire questions about nausea and bowel movements.

I met Marlene when her dreams were interrupted at 5 a.m. Monday morning. She opened her eyes to a swarm of white coats crowding around her bed. She then weathered a few minutes of rapid-fire questions about nausea and bowel movements.

It was morning rounds on my first day of my surgery rotation at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Marlene was much more accustomed to this whirlwind pre-dawn ritual than I. She had been in the hospital since Friday, when she had decided that the past week of vomiting and abdominal pain warranted a trip to the emergency room.

She was concerned that she hadn’t had a bowel movement in a week, and she was even more worried because her doctors were worried. She was wary of surgery, but she agreed that a trip to the operating room made sense.

That way, we could identify why her bowels were blocked and fix the problem. Having undergone a major operation 18 months before to remove a pancreatic tumor, she was resolute but scared. She knew how difficult post-surgical rehabilitation could be, and, at 73 years old, she wondered if she had the strength. Despite her ambivalence, she gamely grinned to the swarm of white coats and thanked us as we shuffled away.

A few hours later, I met her in the cavernous holding area adjacent to the operating rooms. When I introduced myself to her, she smiled broadly and squeezed my hand. She was very scared, she told me, but she was ready. Over the next few minutes, we wheeled her to the operating room, the anesthesiologists injected their medicines, and the surgeons had begun to cut.

The surgery itself was straightforward. A few errant strands of scar tissue had formed after her previous operation, and now they were tangled around her bowel. Snipping these bands of scar tissue allowed the bowel to untangle, relieving the blockage.

After Marlene’s anesthesia wore off and she moved to the post-anesthesia care unit, her surgeons told Marlene that everything went well. She was even more anxious than she had been before the surgery, though. I stood at her side for ten more minutes, repeating the words of reassurance from her surgeons that she would feel better soon. She squeezed my hand and told me that she hoped I was right, but that she wasn’t so sure.

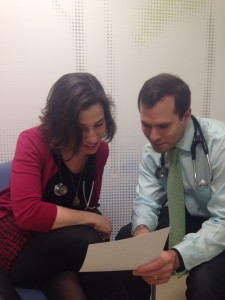

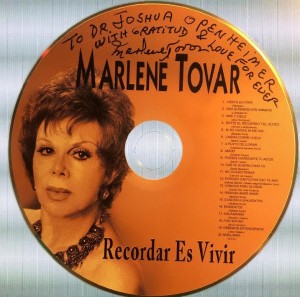

Over the next eight days, through bedside chats and strolls across the ward, Marlene told me that she was slowly feeling better. She regained some energy and began eating food again, first juice, then pudding and scrambled eggs, and finally regular meals. She also told me stories about her life’s adventures. As a Colombian pop singer decades before, she had toured Latin America extensively and traveled the world.

Eventually it was time to go home. Marlene became nervous again, wondering whether she would get worse after leaving the hospital. When I offered to call her in a few days, she said she looked forward to my call.

It was easy to tell over the phone that she was smiling once again, and she was eager to tell me how much she had been walking and eating on her own. She also asked me whether I was free in four weeks. The Colombian Consulate would be hosting a cocktail hour in her honor, prior to her receiving a lifetime achievement award at Lincoln Center, and she invited me and my girlfriend to attend.

When Elizabeth and I walked into the Consulate, Marlene greeted us with that familiar smile. And yet she was transformed. Her sequined suit complemented her personality far better than the faded blue hospital gown had. And instead of drinking apple juice, she sipped from a glass of wine.

Marlene Tovar consented to being represented in this post.