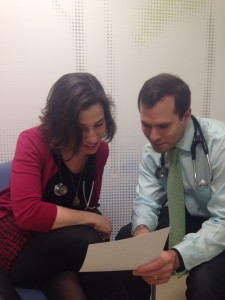

Alexandra Bachorik, MD Student, Class of 2015, reflects on her participation in the Interclerkship Ambulatory Care Track (InterACT). InterACT is a 13-week integrated clerkship which provides select third-year medical students with a longitudinal clinical experience grounded in the foundations of ambulatory medicine, chronic illness care and care for vulnerable persons.

Alexandra Bachorik, MD Student, Class of 2015, reflects on her participation in the Interclerkship Ambulatory Care Track (InterACT). InterACT is a 13-week integrated clerkship which provides select third-year medical students with a longitudinal clinical experience grounded in the foundations of ambulatory medicine, chronic illness care and care for vulnerable persons.

The variation of the InterACT week forced me both to appreciate the differences and, perhaps more importantly, the similarities of the clinical approach across different settings.

Early in my InterACT weeks, a mentor said to a pediatrics resident within my earshot “you have to remember to approach a patient in a developmentally appropriate way.” For most third-year medical students, the concept of development—asking about the patient’s development of new skills, achievement of motor, language and social skills—is something largely limited to the 6 week pediatrics clerkship. By contrast, as I maneuvered through my 13 weeks of InterACT, shifting from vascular surgery to Visiting Doctors to pediatrics, the developmental history kept dropping in and out of my history taking. While at first, it was simply a question of remembering to take a developmental history in pediatrics clinic and a geriatric review of systems in geriatrics clinic, the broader lesson over the course of the year was to vary my history, exam and note to suit a particular clinical setting.

Though I (relatively) quickly learned to maneuver between different clinical scenarios, there were tired and scatterbrain days when I had trouble switching gears. On one occasion, I took a developmental history from an adult, something I initially considered an error. Upon reflection, it seems not an error, but an accidental realization meaning of my mentor’s statement. We must consider ALL patients, not merely pediatric ones, as developing individuals if we are to provide meaningful care to them. Children aren’t the only patients for whom the development and maintenance of skill sets and achievement of milestones is important. One of my adult patient’s alcoholism has cost him a job, and briefly his home and his marriage. Securing a job and participating successfully in relationships are certainly milestones of adulthood, though we’re never taught to think of questions of occupation and marital status as a developmental history, per se, for adults. However, just as a failure to achieve milestones is something we investigate in children as an indicator of underlying pathology, so should it be in adults. For my alcoholic patient, his loss of these milestones indicates not only the organic effects of alcohol, but also resignation and a sense of lost potential. To treat him appropriately, the conversation had to focus on motivation, on his assuming some degree of adult responsibility for his well-being. In this way, the diversity of experiences in InterACT has shown me that tailoring a clinical approach doesn’t just mean trading out our pediatric toolbox for our adult toolbox when we change settings. Rather, it has taught me that we should keep all of our clinical tools together, and use any and all clinical tools appropriate for the patient in front of us, regardless of which box the tool originally came from.

During its first 4 years (2010-2014) InterACT was fully funded with a grant from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation titled: Educating Future leaders in the Primary Care of Persons with Chronic Illnesses and the Medically Disenfranchised through Longitudinal Clinical Experiences.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alexandra Bachorik is an MD Student, Class of 2015 at the Icahn School of Medicine.